The Story of Augustus Lebourdais

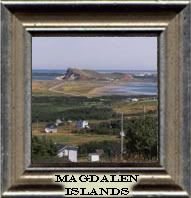

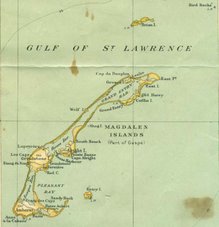

For the most part, this is a true story, but I have taken some liberties with the dates, for which I didn't feel like looking up at this time. The story was wrote as a story for Writers Island and there was considered to be fiction, so I didn't need to worry about exact details. However, because it is a story of the Magdalen Islands, I decided to put it here also.

The SnowmanLong ago, in the year 1873, a ship coming down the river of Saint Lawrence, ran head on into a disastrous hurricane as it approached the north dunes of the Magdalen Islands. The cold December winds had been coming up from the south, so the Captain of the sailing schooner Wasp had decided to stay the ship on North. But as history tells it, the wind shifted as the ship approached the center of the islands and blew with such force, that the ship foundered on Shoal's reef. Before long, the ship fell apart, and 19 of the 20 seamen on board were soon lost.

One man however, the first mate, managed to cling to one of the broken ships masts and was pushed ashore, through sea ice and broken slush. He was frozen and encrusted with ice but still crawled up the sand and roll down the other side of a sand hill. There he laid until morning.

Some young people came as soon the light of day approached, for shipwrecks were common on the islands, in those days and interesting and much needed salvage could be found. As they approached the sand hill, the man raised up his towering form to eight feet and scared the boys who ran off to tell their fathers about the big foot snowman on the beach. At first they were scoffed at but the priest decided to go look at the monstrosity. All he found were footprints, the length of a yard-stick amongst the flotsam of ship wreckage, and he prayed.

The men came and they followed the prints, remembering another haunting story, of another victim whom they thought was not Christian so they had buried him face down in a sand hill, because the color of his skin was black. But he kept being uncovered by the wind though the people thought he dug himself out and they were afraid of the unnatural. Three times he had been buried and three times the dead man rose from the sand and haunted the families of the small village nearby, with eerie crying wails, until finally they gave him a decent Christian burial in the catholic cemetery.

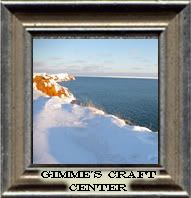

The yard-long foot steps disappeared and they lost their quarry, so they headed home to face another brutal night of wicked northerly winds with and freezing sleet. Once again that night the people of the vi llage heard wails and screams of the haunted nearby. Fearful, the priest with a group of men with lanterns, searched around the homes and barns trying to find the source of the wailing and by lamp light they found the yard-long foot prints in drifts of snow, near large stacks of hay. Behind one of these stacks they found a snowman, eight-feet tall, lying on its side where it had fallen. The snow moved and moaned and the men cried and ran for the priest to save them from the unnatural beast.

llage heard wails and screams of the haunted nearby. Fearful, the priest with a group of men with lanterns, searched around the homes and barns trying to find the source of the wailing and by lamp light they found the yard-long foot prints in drifts of snow, near large stacks of hay. Behind one of these stacks they found a snowman, eight-feet tall, lying on its side where it had fallen. The snow moved and moaned and the men cried and ran for the priest to save them from the unnatural beast.

llage heard wails and screams of the haunted nearby. Fearful, the priest with a group of men with lanterns, searched around the homes and barns trying to find the source of the wailing and by lamp light they found the yard-long foot prints in drifts of snow, near large stacks of hay. Behind one of these stacks they found a snowman, eight-feet tall, lying on its side where it had fallen. The snow moved and moaned and the men cried and ran for the priest to save them from the unnatural beast.

llage heard wails and screams of the haunted nearby. Fearful, the priest with a group of men with lanterns, searched around the homes and barns trying to find the source of the wailing and by lamp light they found the yard-long foot prints in drifts of snow, near large stacks of hay. Behind one of these stacks they found a snowman, eight-feet tall, lying on its side where it had fallen. The snow moved and moaned and the men cried and ran for the priest to save them from the unnatural beast.The priest used all his holy water to bless the strange mass before realizing that there was a man, as human as he under all the ice and snow. As quickly as they could, they brought him to the warmth of the parsonage to thaw the snow man out. The pain and screams as the man’s limbs thawed haunted the priest for the rest his natural life. The tales of the eight-foot snowman that came to life haunted the villagers for many generations to come. But for Augustus LeBourdais, his life had just began as if he had been re-born and for islanders who were fortunate enough to work with this man, well..., they too, have gone down in history as being men of vision, who brought the islands into the twentieth century, by bringing the telegraph system to the Magdalens.

The priest and a few of the men had to saw the man's feet off because they had been frozen beyond rejuvenation. They did this without the benefit of anesthesia and when the spring thaw came they sent him to Quebec City, where he had the rest of his legs removed, just below the knees. Augustus returned to the Magdalen Islands, to marry one of the village girls whom he fell deeply in love with, during that long cold winter.